Jon Hendricks

| Jon Hendricks | |

|---|---|

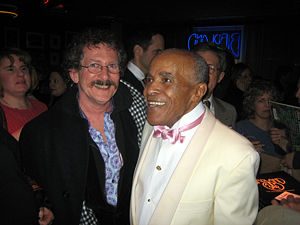

Hendricks in 2008

|

|

| Background information | |

| Born | September 16, 1921 Newark, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | November 22, 2017 (aged 96) Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Genres | Jazz |

| Occupation(s) | Singer, lyricist |

| Years active | 1957–2017 |

John Carl Hendricks (September 16, 1921 – November 22, 2017), known professionally as Jon Hendricks, was an American jazz lyricist and singer. He is considered one of the originators of vocalese, which adds lyrics to existing instrumental songs and replaces many instruments with vocalists (such as the big-band arrangements of Duke Ellington and Count Basie). Furthermore, he is considered one of the best practitioners of scat singing, which involves vocal jazz soloing. For his work as a lyricist, jazz critic and historian Leonard Feather called him the “Poet Laureate of Jazz”, while Time dubbed him the “James Joyce of Jive”. Al Jarreau called him “pound-for-pound the best jazz singer on the planet—maybe that’s ever been”.[1]

Contents

[hide]

Early years[edit]

Born in 1921 in Newark, Ohio, Hendricks and his 14 siblings moved many times, following their father’s assignments as an A.M.E. pastor, before settling permanently in Toledo. There, Hendricks began his singing career at the age of seven. He has said: “By the time I was 10, I was a local celebrity in Toledo. I had offers to go with Fats Waller when I was 12, and offers to go with Ted Lewis and be his shadow when I was 13. He had that song ‘Me and My Shadow‘. And he had this little Negro boy who was his shadow, that did everything he did. That was his act.”[2] As a teenager, Jon’s first interest was in the drums, but before long he was singing on the radio regularly with another Toledo native, pianist Art Tatum. Jon met his first wife Colleen Moore in Toledo, Ohio. They were married and had 4 children, Jon Jr., Colleen, Eric and Michelle.

World War II[edit]

After serving in the Army during World War II, Hendricks went home to attend University of Toledo on the G.I. Bill as a pre-law major. Just when he was about to enter the graduate law program, the G.I. benefits ran out. Charlie Parker had, at a stop in Toledo two years prior, encouraged him to come to New York and look him up. Hendricks moved there and began his singing career.

Lambert, Hendricks and Ross[edit]

In 1957, he teamed with Dave Lambert and Annie Ross to form the legendary vocal trio Lambert, Hendricks & Ross (LH&R). With Jon as lyricist, the trio perfected the art of vocalese and took it around the world, earning them the designation of the “Number One Vocal Group in the World” for five years in a row from Melody Maker magazine. Their multi-tracked album Sing a Song of Basie was one of the earliest examples of overdubbing.[3] Hendricks typically wrote lyrics not just to melodies but to entire instrumental solos, a notable example being his take on Ben Webster‘s tenor saxophone solo on Ellington’s original recording of “Cotton Tail“, as featured on the album Lambert, Hendricks and Ross! (1960). His lyrics to Benny Golson‘s “I Remember Clifford” have been recorded by several other vocalists, including Dinah Washington, Carmen McRae, Nancy Wilson, Ray Charles, The Manhattan Transfer and Helen Merrill. After six years the trio disbanded for solo careers but not before leaving behind a catalog of legendary recordings, most of which have never gone out of print.

Countless singers cite the work of LH&R as an influence, including Van Morrison, Al Jarreau and Bobby McFerrin. The song “Yeh Yeh“, for which Hendricks composed the lyrics, became a 1965 hit for British R&B-jazz singer Georgie Fame, who continues to record and perform Lambert, Hendricks & Ross compositions to this day. In 1966 Hendricks recorded “Fire in the City” with the Warlocks, who shortly after changed their name to the Grateful Dead.[4] Hendricks wrote lyrics for several Thelonious Monk songs, including “In Walked Bud“, which he performed on Monk’s 1968 album Underground.

For a performance at the 1960 Monterey Jazz Festival, he created and starred in a musical he called Evolution of the Blues Song, which featured such acclaimed singers as Jimmy Witherspoon, Hannah Dean, and “Big” Miller, as well as saxophonists Ben Webster and Pony Poindexter. The ensemble played not only Hendricks’ words and music but also Percy Mayfield‘s classic “Please Send Me Someone to Love,” the driving D. Love gospel song “That’s Enough”, and the blues evergreen, “C.C. Rider“. In 1961, Columbia Records released an LP of the production and Hendricks later presented the show in San Francisco; at the Westwood Playhouse in Los Angeles, where it was produced by attorneys Burton Marks and Mark Green; and in New York City.

Solo[edit]

Pursuing a solo career, and after divorcing his first wife, Colleen, Hendricks moved his children to London, England, in 1968, partly so that his four children could receive a better education. While based there he toured Europe and Africa, performed frequently on British television and appeared in the 1971 British film Jazz Is Our Religion (which focuses on the photographs of Val Wilmer) as well as the French film Hommage à Cole Porter. His sold-out club dates drew fans such as the Rolling Stones and the Beatles. Five years later the Hendricks family settled in Mill Valley, California, where Hendricks worked as the jazz critic for the San Francisco Chronicle and taught classes at California State University at Sonoma and the University of California at Berkeley. The piece he wrote for the stage about the history of jazz, Evolution of the Blues, ran for five years at the Off-Broadway Theatre in San Francisco and another year in Los Angeles. His television documentary Somewhere to Lay My Weary Head received Emmy, Iris and Peabody awards.

Hendricks recorded several critically acclaimed albums on his own, some with his wife Judith and daughters Michele and Aria contributing. He collaborated with old friends The Manhattan Transferfor their seminal 1985 album, Vocalese, which won seven Grammy Awards. He served on the Kennedy Center Honors committee under Presidents Carter, Reagan, and Clinton.

In 2000 Hendricks returned to his home town to teach at the University of Toledo, where he was appointed Distinguished Professor of Jazz Studies and received an honorary Doctorate of the Performing Arts. He was selected to be the first American jazz artist to lecture at the Sorbonne in Paris. His 15-voice group, the Jon Hendricks Vocalstra at the University of Toledo, performed at the Sorbonne in 2002. Hendricks also wrote lyrics to some classical pieces including “On the Trail” from Ferde Grofe‘s Grand Canyon Suite. The Vocalstra premiered a vocalese version of Rimsky-Korsakov‘s “Scheherazade” with the Toledo Symphony.

In the summer of 2003 Hendricks went on tour with the “Four Brothers”, a quartet consisting of Hendricks, Kurt Elling, Mark Murphy and Kevin Mahogany. He worked on setting words to and arranging Rachmaninoff’s second piano concerto as well as on two books, teaching and touring with his Vocalstra. He appeared in a film with Al Pacino, People I Know (2002), and also in White Men Can’t Jump (1992).

In 2012, Hendricks appeared in the documentary film No One But Me, discussing his former bandmate and friend, Annie Ross.[5] In 2015, Hendricks lost his second wife Judith to a brain tumor.

Hendricks also appeared on three tracks from the 2016 release of the JC Hopkins Biggish Band titled “Meet Me At Minton’s”. He performs vocalese on “Suddenly (In Walked Bud)”, is included in the ensemble on the album’s title track “Meet Me At Minton’s”, and croons a duet of the Monk tune “How I Wish (Ask Me Now)” with singer and 2016 Thelonius Monk Competition winner Jazzmeia Horn. At the time of the recording he was 93 and Horn was 23. [6]

In 2017, Hendricks’ full lyricization of the album Miles Ahead, including Miles Davis‘ solos and Gil Evans‘ orchestrations, was completed. It was premiered in New York by UK-based choir the London Vocal Project, with Hendricks in attendance, with a studio recording to follow.[7][8]

Hendricks died on November 22, 2017 in Manhattan, New York City.[9]

Discography[edit]

- Evolution of the Blues Song (1959, Columbia Records) [10]

- A Good Git-Together (1959, Pacific Jazz)

- ¡Salud! João Gilberto, Originator of the Bossa Nova (1961, Reprise Records)

- Fast Livin’ Blues (1962, Columbia) [11]

- Recorded in Person at the Trident (1965, Smash Records) [12]

- Jon Hendricks Live (1970, Fontana) [13]

- Times of Love (1972, Muse Records) [14]

- Tell Me the Truth (1975, BMG Records) [15]

- September Songs (1975, Stanyan Records) [16]

- Cloudburst (1982, Enja Records), recorded live at the Domicile, Munich [17]

- Freddie Freeloader (1990, Denon Records) [18]

- Boppin’ at the Blue Note (1994, live, Telarc Records)

- Appears on

- George Russell – New York, N.Y. (1959, Decca)

- Thelonious Monk – Underground (1968, Columbia)

- Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers – Buhaina (Prestige, 1973)

- Jimmy Rowles and Stan Getz – The Peacocks (Columbia, 1975)

- Duke Ellington, Harry James, Herb Pomeroy, Jon Hendricks – Europa Jazz (Europa Jazz EJ 1022, 1981)[19]

- The Manhattan Transfer – Vocalese

- Dave Brubeck – Young Lions & Old Tigers (1995, Telarc)

- The Legacy Lives On (2001, Mack Avenue Records)

- 3 Cohens – Family (2011, Anzic Records) [20]

- Sing a Song of Basie (1957)

- Sing Along with Basie (1958, Roulette)

- The Swingers! (1958)

- Lambert, Hendricks, & Ross! (aka “The Hottest New Group In Jazz”) (1960)

- Lambert, Hendricks & Ross Sing Ellington (1960)

- The Real Ambassadors (1962)

- High Flying with Lambert, Hendricks & Ross (aka The Way-Out Voices of Lambert, Hendricks and Ross) (1962)

- with Lambert, Hendricks and Bavan

- Live at Basin Street East (1963, live)

- At Newport ’63 (1963, live)

- Havin’ a Ball at the Village Gate (aka Lambert, Hendricks and Bavan at the Village Gate) (1964, live)

Filmography[edit]

- The Steve Allen Plymouth Show Episode #4.11 (1958): Lambert, Hendricks & Ross [21]

- NET Playhouse Duke Ellington – A Concert of Sacred Music (1967): Jon Hendricks [22]

- Jazz Is Our Religion (1972) [23]

- White Men Can’t Jump (1992): one of the Venice Beach Boys [24]

- Foreign Student (1994): April’s Father [25]

- Jon Hendricks, Tell Me The Truth, a documentary about the artist, directed by Audrey Lasbleiz (2008, production Mosaïque Films, Paris).

- Blues March: Soldier Jon Hendricks, a documentary about the artist fighting on two fronts in World War II by Malte Rauchof ( Strandfilm Productions (2009)

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Artist Confidential interview with Al Jarreau. XM Radio, 2007.

- Jump up^ Peter B. King, “Jon Hendricks still treasure of jazz world”, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 12, 1994. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- Jump up^ “Behind the Curtain – Jon Hendricks”, OnStage at the Kennedy Center. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- Jump up^ Grateful Dead (5 December 1966). “Grateful Dead Live at Studio on 1966-12-05”. Retrieved November 23, 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- Jump up^ The contributors, No One But Me.

- Jump up^ Jazz, All About. “JC Hopkins Biggish Band: Meet Me At Minton’s”. All About Jazz. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- Jump up^ “After 50 Years, Hendricks’ ‘Miles Ahead’ Remake Set for NYC Premiere”, DownBeat, February 7, 2017/

- Jump up^ “Jon Hendricks’ Miles Ahead”, London Vocal Project.

- Jump up^ Keepnews, Peter (November 22, 2017). “Jon Hendricks, 96, Who Brought a New Dimension to Jazz Singing, Dies”. The New York Times. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- Jump up^ Evolution of the Blues promo-LP 1959, Columbia Records (CS 8383), Discogs.

- Jump up^ Fast Livin’ Blues 4-released-versions 1962, Columbia Records, Discogs.

- Jump up^ Recorded in Person at the Trident 3-released-versions 1965, Smash Records / Philips, Discogs.

- Jump up^ Jon Hendricks Live vinyl 1970, Fontana (6438 019) UK, Discogs.

- Jump up^ Times of Love 2-released-versions 1972, Philips / Applause, Discogs.

- Jump up^ Tell Me The Truth 4-released-versions 1975, Arista / BMG, Discogs.

- Jump up^ September Songs vinyl 1975, Stanyan Records (SR 10132) US, Discogs.

- Jump up^ Cloudburst 3-released-versions 1972, Enja Records / PGP RTB, Discogs.

- Jump up^ Freddie Freeloader CD 1990, Denon (CY-76302) Japan, Discogs.

- Jump up^ “Duke Ellington, Harry James, Herb Pomeroy, Jon Hendricks – Europa Jazz”. discogs.com. Retrieved November 19,2016.

- Jump up^ Astarita, Glenn (January 4, 2012). “3 Cohens: Family (2011)”. All About Jazz. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- Jump up^ The Steve Allen Plymouth Show Episode #4.11, 1958-November-23 (Lambert, Hendricks & Ross), IMDb.

- Jump up^ NET Playhouse Season 1 Episode 34, 1967-June-16 (Jon Hendricks), IMDb.

- Jump up^ Jon Hendricks Filmography, IMDb.

- Jump up^ White Men Can’t Jump 1992-March-27 (Jon Hendricks), IMDb.

- Jump up^ Foreign Student 1994-July-29 (Jon Hendricks), IMDb.

External links[edit]

- On Stage at the Kennedy Center: The Mark Twain Prize 2002 – Behind the Curtain – Jon Hendricks from PBS

- Prototype Online: Inventive Voices podcast featuring an interview with Jon Hendricks – From the Smithsonian’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation website.