Charles Burrell (musician) nous a quittés RIP 104 YEARS

Charles Burrell (musician)

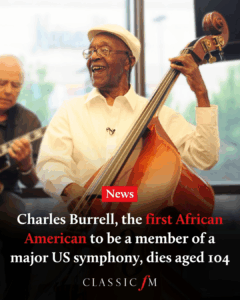

Charles Burrell (October 4, 1920 – June 17, 2025) was an American classical and jazz bass player most prominently known for being the first African American to be a member of a major American symphony (the Denver Symphony Orchestra, now known as the Colorado Symphony). For this accomplishment, he is often referred to as « the Jackie Robinson of Classical Music ».[1][2][3]

Early life, family and education

[edit]

Charles was born in Toledo, Ohio, and raised in Depression-era Detroit, Michigan. His mother, Denverado, was the daughter of an African Methodist Episcopal Church minister from Denver, Colorado.[4]

In grade school, Charles excelled in music. When he was twelve years old, he heard the San Francisco Symphony under renowned conductor Pierre Monteux on his family’s crystal radio and vowed to one day play as a member of the orchestra under his direction.[4] He played bass as a student at Cass Tech High School, where he was instructed by two musicians from the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, Gaston Brohm and Oscar Legassy.[4]

Burrell attended the New England Conservatory of Music, and after his honorable discharge from military service in the US Navy, he attended Wayne State University.[5] He earned a teaching certificate at University of Denver.[5]

Career

[edit]

After high school, Burrell landed a job playing jazz at B.J.’s, a club in Detroit’s Paradise Valley. At the start of World War II, he was drafted into an all-black unit located at Great Lakes Naval base near Chicago, Illinois. He played in the unit’s all-star band with Clark Terry, Al Grey, and O. C. Johnson,[6] and attended classes at Northwestern University and with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

In 1949, Burrell joined his mother’s relatives in Denver, Colorado.[4] While earning his teaching certificate, he worked at Fitzsimons Army Hospital, and later taught in Denver public schools.[5] He became the first African-American in the Denver Symphony Orchestra.[7] According to the book Music for a City Music for the World: 100 Years with the San Francisco Symphony, while on vacation in San Francisco, he charmed his way into an audition with the orchestra after a chance meeting in the street with Philip Karp, the principal bassist for the Symphony.[8] In 1959, he fulfilled his dream of playing for Pierre Monteux by joining the San Francisco Symphony as its first African-American musician,[7] and he remained there until 1965.[9] Returning to Denver, he re-joined its symphony orchestra, playing with them for decades, retiring in 1999.[7]

Burrell was the first African-American to become a member of such a prestigious orchestra, and thus has been referred to as « the Jackie Robinson of classical music ».[10][1][2][3][8][11][7][a]

According to Jet magazine and Indianapolis Recorder articles in 1953, Burrell quit playing in the Denver Symphony to become the bass player in Nellie Lutcher‘s band.[12][13] He was a prominent jazz player in the scene of Five Points, Denver and was featured in the PBS documentary on the subject.[14][5] At that time, the jazz scene in Five Points was the only one between St. Louis and the West Coast, so it became one of the most alive in the country, often being referred to as « The Harlem of the West ». He played in the first integrated jazz trio in Colorado, the Al Rose Trio.[15][7][16] He rose to be a central player in the Five Points jazz scene by becoming the house bass player at the Rossonian Hotel, considered the « entertainment central » spot in Five Points during that era.[17] He shared the stage with jazz legends such as Fats Waller,[7] Billie Holiday, Erroll Garner, Charlie Parker, Earl Hines, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Lionel Hampton[11], as well as Gene Harris.[18]

He was also noted as the teacher and mentor of bass player Ray Brown and multi-Grammy Award-winning vocalist Dianne Reeves, a niece of his.[11][19] Keyboardist George Duke, a cousin, also credited Burrell for being the person that convinced him to give up classical music and switch to jazz.[20][21] Duke explained that he « wanted to be free » and Burrell « more or less made the decision for me » by convincing him to « improvise and do what you want to do ».

He continued to perform well into his 90s, including playing live in the studio of prominent Jazz radio station KUVO,[22] and was one of the two grand marshals that led the kick-off parade at the Five Points Jazz Festival.[23][24] In 2021, he appeared in the documentary film JazzTown.[citation needed]

Death

[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2025)

|

Burrell died on June 17, 2025, at the age of 104.[25]

Awards and tributes

[edit]

- In 2008, he received a Denver Mayor’s award for excellence in Arts and Culture.[26]

- In 2011, he received a Martin Luther King Jr. humanitarian award.[27]

- Prominent Jazz radio station KUVO broadcast a tribute concert to him on his birthday.[28]

- Congresswoman Diana DeGette also led a tribute to him on the floor of the United States House of Representatives in honor of his 90th birthday, referring to him as a « titan of the classical and jazz bass ».[7]

- The Alphonse Robinson African-American Music Association named the « Charles Burrell Award » after him.[2]

- In November 2017, he was inducted into the Colorado Music Hall of Fame.[29]

- In 2021, Aurora Public Schools in Colorado announced that their new arts magnet school would be named after him.[30] The Charles Burrell Visual and Performing Arts Campus opened for the 2022–2023 school year.

Discography

[edit]

- Don Ewell: Denver Concert (Pumpkin)

- Marie Rhines : Tartans & Sagebrush (Ladyslipper)[31]

- Whiskey Blanket: No Object

- Joan Tower / Colorado Symphony Orchestra, Marin Alsop – Fanfares For The Uncommon Woman (Koch International Classics)[32]

Bibliography

[edit]

- Burrell, Charlie; Handelsman, Mitch (2014). The Life of Charlie Burrell: Breaking the Color Barrier in Classical Music.

Notes

[edit]

- ^ Prominent African-American classical musicians preceding Burrell by approximately a century include composer Francis Johnson, classical guitarist Justin Holland, and National Peace Jubilee grand orchestra members Frederick E. Lewis and Henry F. Williams.

References

[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b de Yoanna, Michael (December 4, 2014). « Charlie Burrell, pioneer black musician in Colorado, releases memoir ». cpr.org. Colorado Public Radio.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Hudson, Andrew; Steen, Purnell. « Charlie Burrell: A Denver Musical Legend ». Denver Urban Spectrum. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Williams, Emily (December 1, 2014). « Professor releases book on life of renowned local artist Charles Burrell ». news.ucdenver.edu. University of Colorado Denver. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d « Charles Burrell ». thehistorymakers.org. The History Makers. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d DeGette, Diana (February 11, 2011). « Tribute to Mr. Charlie Burrell » (PDF). Congressional Record. 157 (22). United States Congress: E211. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 4, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2025 – via congress.gov.

- ^ « Band of brothers ». NWI Times. March 2, 2003.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g DeGette, Diana (February 11, 2011). « Tribute to Mr. Charlie Burrell ». Congressional Record. 157 (22): E211 – E212 – via govinfo.gov.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rothe, Larry (July 22, 2011). Music for a City Music for the World: 100 Years with the San Francisco Symphony. Chronicle Books. p. 56. ISBN 9781452110240 – via Google Books.

- ^ « San Francisco Symphony Orchestra Musicians List ». stokowski.org. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023.

- ^ « Charles Burrell: The Jackie Robinson of Classical Music ». sfsymphony.org. San Francisco Symphony. February 2, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c « Bass player Charlie Burrell lays foundation for classical, jazz followers ». Denver Post. June 18, 2011.

- ^ Robinson, Major (July 23, 1953). « New York Beat ». Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. p. 39 – via Google Books.

- ^ Womack, Bob (July 25, 1953). « Musical Upbeat ». Indianapolis Recorder. p. 13. Retrieved June 19, 2025 – via Hoosier State Chronicles, newspapers.library.in.gov.

- ^ « RMPBS Specials | Rocky Mountain Legacy: Jazz in Five Points | Season 1 | Episode 105 ». PBS.org. February 20, 2014.

- ^ « The Jazz Roots of Denver’s Five Points, Uncovered ». Innovators Peak. February 25, 2016.

- ^ Handy, D. Antoinette (November 30, 1998). Black Women in American Bands and Orchestras. Scarecrow Press. p. 19. ISBN 9780810834194 – via Google Books.

- ^ « Five Points Glory Days » (PDF). Front Porch Stapleton. February 2008.

- ^ Harris, Janie; Evancho, Bob (November 30, 2005). Elegant Soul: The Life and Music of Gene Harris. Caxton Press. p. 90. ISBN 9780870044458 – via Google Books.

- ^ « Dianne Reeves Celebrates Grammy Award at Hartford’s Infinity Music Hall ». Connecticut Public. February 10, 2015.

- ^ Coryell, Julie; Friedman, Laura (November 30, 2000). Jazz-rock Fusion: The People, the Music. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 192. ISBN 9780793599417 – via Google Books.

- ^ « Legendary Jazz Artiste George Duke’s Final Bow ». The Standard. August 18, 2013.

- ^ « Renowned bassist Charles Burrell bangs out the bass with vocalist… » gettyimages.com. Getty Images. October 14, 2002.

- ^ Solomon, Jon; Moulton, Katie (May 17, 2016). « Five Points Jazz Festival and Project Pabst Come to Denver This Weekend ». Westword.

- ^ « Five Points Jazz 2016 ». KUVO Jazz. May 4, 2016.

- ^ DeMare, Kiara (June 17, 2025). « Classical bass legend Charlie Burrell dies at 104 ». Colorado Public Radio.

- ^ « Past Honorees – Mayor’s Awards ». Denver Arts and Venues. 2008.

- ^ « Eight Martin Luther King Jr. Awards presented at reception, concert ». Denver Post. January 15, 2015.

- ^ « Tribute to Charles Burrell today at 4pm ». KUVO Jazz. October 1, 2014.

- ^ « Charles Burrell ». Colorado Music Hall of Fame. November 28, 2017.

- ^ Duncombe, Claire (November 19, 2021). « Visual and Performing Arts Campus Named for Charles Burrell ». Westword.

- ^ « Marie Rhines – Tartans & Sagebrush (1982, Vinyl) ». Discogs. 1982.

- ^ « Joan Tower / Colorado Symphony Orchestra, Marin Alsop – Fanfares For The Uncommon Woman (1999, CD) ». Discogs. 1999.

External links

[edit]

- Charles Burrell discography at Discogs

- Charles Burrell at AllMusic

- Charles Burrell at IMDb

- Documentary: Charlie Burrell, American symphonies’ first black musician at denverite.com

- Documentary on Jazz in Five Points at PBS.org

- Documentary Series Voices of the Civil Rights Movement: Integrating a Major U.S. Symphony

- Television broadcast of the Charlie Burrell Trio on Glenarm Place (1983), KRMA

- 1920 births

- 2025 deaths

- American jazz bass guitarists

- American male bass guitarists

- Musicians from Toledo, Ohio

- African-American jazz musicians

- African-American classical musicians

- Northwestern University alumni

- 20th century in San Francisco

- Musicians from the San Francisco Bay Area

- 20th-century American bass guitarists

- Jazz musicians from California

- Guitarists from Ohio

- Guitarists from California

- Jazz musicians from Ohio

- Classical musicians from California

- Classical musicians from Ohio

- 20th-century American male musicians

- American male jazz musicians

- African-American centenarians

- American men centenarians

- African-American guitarists

- United States Navy personnel of World War II

- 20th-century African-American musicians

- 21st-century African-American musicians